Financial computing is a cornerstone of the modern financial industry, driving everything from high-frequency trading to complex risk management. Speed is critical in this domain, where milliseconds can mean the difference between profit and loss. This article explores the key factors that make financial computing fast, focusing on the delicate balance between precision and accuracy, algorithm optimization, and hardware acceleration.

Balancing Precision and Accuracy

In financial computing, precision refers to the detail level in numerical calculations, while accuracy refers to how close those calculations are to the true value. Finding the right balance between these two can significantly impact computational speed. High precision often means more computational resources and time, which can slow down processes. Conversely, reduced precision can speed up calculations but may lead to less accurate results. Financial engineers must evaluate the specific requirements of their applications to determine the optimal level of precision.

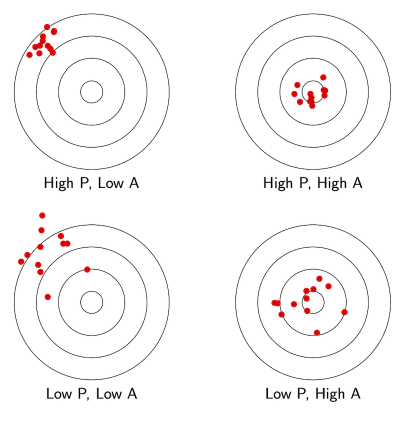

Illustrating the distinction between precision P and accuracy A.

For instance, in high-frequency trading (HFT), speed is paramount. Traders often accept lower precision in exchange for faster execution times, as minor inaccuracies are outweighed by the advantage of speed. In contrast, risk management requires high precision to accurately predict potential losses and ensure regulatory compliance. However, even in this domain, computational speed remains important to process large datasets efficiently.

Definitions: Precision and Accuracy

Precision refers to the detail with which a numerical value is expressed. It focuses on the consistency and repeatability of measurements. If you perform the same calculation multiple times, precision describes how close the results are to each other. In the context of floating-point arithmetic, single-precision (32-bit) and double-precision (64-bit) represent different levels of precision, with precision often related to the number of significant digits in a number.

Accuracy, on the other hand, refers to how close a computed or measured value is to the true or actual value. If you calculate the price of an option using a model, accuracy describes how close your calculated price is to the true market price. Accuracy is affected by both systematic errors (bias) and random errors in measurements or calculations.

Precision vs. Accuracy: Key Differences

Precision focuses on the consistency of results. High precision means values are very close to each other but not necessarily close to the true value. For example, if you calculate an option price repeatedly with a model that always gives values close to each other, but the model has a bias, those values may not be accurate.

Accuracy focuses on the correctness of the results. High accuracy means values are close to the true value but not necessarily consistent with each other. For instance, using different models to calculate an option price where one model gives a value close to the true market price, even if different models give varying results, demonstrates high accuracy but low precision.

Example 1

Let’s say we are pricing a European call option using Monte Carlo simulations.

Using single-precision, the results might be $10.24, $10.23, and $10.25, while with double-precision, the results could be $10.241732, $10.241730, and $10.241731.

In this case, the double-precision results are more precise because they show more significant digits and are more consistent.

Example 2

Assume the true market price of an option is $10.30.

If Model A produces results such as $9.80, $9.81, and $9.79, it is precise because the values are close to each other, but it is not accurate because the values are far from the true price.

Conversely, if Model B produces results such as $10.28, $10.35, and $10.32, it is accurate because the values are close to the true price, but it is not as precise because the values vary more.

Precision is about consistency, while accuracy is about correctness.

When pricing derivatives, having a highly precise model can help reduce the variability of the results, but the accuracy of the model is crucial for making the correct financial decisions. For risk management, both precision and accuracy are important to ensure consistent and reliable risk assessments.

Using single-precision arithmetic can speed up calculations but might reduce both precision and accuracy, depending on the complexity of the model and the range of input values. Double-precision arithmetic can enhance precision and potentially accuracy but at the cost of computational speed and resource usage.

In financial computing, achieving a balance between precision and accuracy is essential for reliable and efficient computational models.

Precision and Accuracy: A Mathematica Approach

In Mathematica, commands like FindRoot and NDSolve utilize options such as WorkingPrecision, PrecisionGoal, and AccuracyGoal to control the numerical accuracy and precision of the computations. Let’s look at an explanation of each option and its use:

WorkingPrecision: The WorkingPrecision option specifies the number of digits of precision to be maintained in the internal calculations. It controls the precision of intermediate steps in the computation. For example, setting WorkingPrecision -> 20 ensures that all calculations are carried out with 20-digit precision. This option is crucial when computations involve very small or very large numbers or when iterative methods are used, as in root-finding or differential equation solving. Higher working precision can help to avoid cumulative rounding errors.

PrecisionGoal: The PrecisionGoal option specifies the number of significant digits of precision sought in the final result. It determines how precisely the final answer is expected to match the exact solution. For instance, setting PrecisionGoal -> 10 means the algorithm will aim for a result with 10 significant digits of precision. This is particularly useful when the result must be correct to a certain number of significant digits, regardless of the scale of the numbers involved. Financial computations often require results accurate to a certain number of significant figures.

AccuracyGoal: The AccuracyGoal option specifies the number of accurate digits in the final result. It controls the absolute error in the final result, aiming for the specified number of accurate digits. For example, setting AccuracyGoal -> 10 means the algorithm will aim for a result with an absolute error less than \(10^{-10}\). This is essential when the result must be within a specific absolute error range, such as in physical simulations where results need to match real-world measurements within a certain error margin.

For FindRoot, consider the function \(f(x) = x^3 - 2x - 5\). You can use FindRoot with specific precision and accuracy goals like this:

f[x_] := x^3 - 2 x - 5

root = FindRoot[f[x], {x, 2}, WorkingPrecision -> 20, PrecisionGoal -> 10, AccuracyGoal -> 10]

For NDSolve, suppose you have a differential equation \(y''[x] + y[x] == 0\) with initial conditions \(y[0] == 1\) and \(y'[0] == 0\). You can solve it with specific precision and accuracy goals as follows:

eq = y''[x] + y[x] == 0;

init = {y[0] == 1, y'[0] == 0};

solution = NDSolve[{eq, init}, y[x], {x, 0, 10}, WorkingPrecision -> 20, PrecisionGoal -> 10, AccuracyGoal -> 10]

The WorkingPrecision option is akin to ensuring you have high-quality tools for a task. Higher working precision can prevent errors from accumulating during the calculations, especially when dealing with very small or very large numbers or iterative methods. The PrecisionGoal is like aiming for exactness in a recipe, where you need a result accurate to a specific number of significant digits. This is crucial for scenarios like financial computations that require a high degree of precision. The AccuracyGoal focuses on the absolute error, ensuring that the result is within a specific error margin, similar to ensuring a dish’s flavor falls within a desired taste range.

Consider calculating the root of \(f(x) = x^3 - 2x - 5\). Using high working precision, you might write:

rootHighPrecision = FindRoot[f[x], {x, 2}, WorkingPrecision -> 50]

This yields a result with very high internal calculation precision, ensuring that the intermediate steps are highly accurate. To set specific goals for precision and accuracy, you could write:

rootWithGoals = FindRoot[f[x], {x, 2}, WorkingPrecision -> 50, PrecisionGoal -> 15, AccuracyGoal -> 15]

This ensures that the final root value is accurate to 15 significant digits and within an absolute error of \(10^{-15}\).

Using these options effectively allows you to balance computational efficiency and numerical accuracy, tailoring the calculations to the specific needs of your problem.

Algorithm Optimization

Optimizing algorithms is another crucial factor in achieving fast financial computing. Efficient algorithms can significantly reduce computation time and resource usage. Advanced numerical methods, such as Monte Carlo simulations and finite difference methods, enhance the efficiency of financial models. Approximation techniques like polynomial approximations and linear interpolations can simplify complex calculations, balancing the need for speed and accuracy.

Consider an option pricing model as a case study. Traditional methods like the Black-Scholes formula can be slow when dealing with large portfolios. However, using optimized algorithms such as the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) for option pricing can dramatically increase speed without sacrificing accuracy.

Hardware Acceleration

Leveraging specialized hardware, particularly Nvidia GPUs, is essential for achieving high-speed financial computing. GPUs excel at parallel processing, handling thousands of simultaneous threads. This makes them ideal for tasks like Monte Carlo simulations, which can be parallelized effectively. In comparison, a typical CPU might handle a few cores processing tasks sequentially, while a GPU can process many cores simultaneously, significantly boosting performance for certain types of financial computations.

Nvidia’s CUDA platform and cuBLAS library provide tools for developers to harness the power of GPUs for financial computing. These tools facilitate the development of high-performance applications by optimizing low-level computations. For AI and machine learning applications in finance, TensorRT optimizes neural network inference, ensuring fast and efficient performance on Nvidia hardware.

Achieving fast financial computing requires a multifaceted approach.

Balancing precision and accuracy ensures that computations are both fast and reliable. Optimizing algorithms reduces computational load and improves efficiency. Finally, leveraging hardware acceleration with Nvidia GPUs provides the necessary performance boost for handling large-scale, complex financial tasks. By focusing on these key areas, financial engineers can develop systems that meet the demanding speed requirements of the financial industry while maintaining the necessary level of precision and accuracy.